Mount is Saudi, not Egyptian

How would you feel if you paid for a travel package to go to Mount Sinai, on the Egyptian peninsula of the same name, and discovered that it was all a mistake, a geographical, historical and archaeological error? You arrived at the Monastery of Santa Catarina, climbed the rocky and arid mountain, prayed thanking you for being where Moses did not receive the Decalogue, wondered how two million people crowded into that inhospitable and inappropriate valley, checked all the “references and historical proofs of the guide” and, upon returning from the adventure, you hear or read that it was all just a fancy slot machine.

Based on the studies of Ronald Eldon Wyatt (despite much criticism against him), the Italian archaeologist and theologian Luigi Caratelli is part of the list of researchers who unraveled the mystery surrounding the most likely location of Mount Sinai. According to Caratelli, the American Ron Wyatt was a former nurse anesthetist who decided to venture as an archaeologist for a decade following the true route of the Hebrew exodus, between 1974 and 1984. Wyatt made many mistakes, but he provided important information for other researchers to follow his hypotheses.

So prestigious by Christians, Muslims and even Israelites, Mount Sinai is not located in the Sinai Peninsula, territory of Egypt, as many people believe. Another geographic point draws attention in light of the new evidence. Based on the reports present in the biblical text and the Torah, the answers appear to be justified. When making an allegorical mention of the covenants, using the names of Abraham’s wife and concubine, the apostle Paul places “Mount Sinai in Arabia” (Gal 4:24-5).

The apostle of the people knew the geography of the Arabian Peninsula very well, as he had lived in the region for three years, preparing to take up the ministry (Gal 1:17-8). Just as Moses had killed an Egyptian and the Lord allowed his escape to the land of Midian (Ex 2:15), Paul had also participated in the murder of Stephen and needed to be shaped to exercise meekness and patience. Moses spent forty years in the desert, but Paul stayed much less, but long enough to describe the places accurately.

Geography of the region

While tending his father-in-law’s flock, Moses headed to the western part of Midian, arriving at Horeb, known as the “mountain of God” (Ex 3:1). Moses’ encounter with the Lord was notable for a pact, a guarantee that, upon leaving Egypt, he and the people of Israel would serve, or worship “God on this mountain” (v. 12). North American researcher Charles C. Robertson maintains that “the position of Horeb, Sinai, is located in the land of Midian, as a historical examination confirms this hypothesis” (On the track of the exodus, p. 87), an opinion corroborated by the Italian Claudio Gherardi.

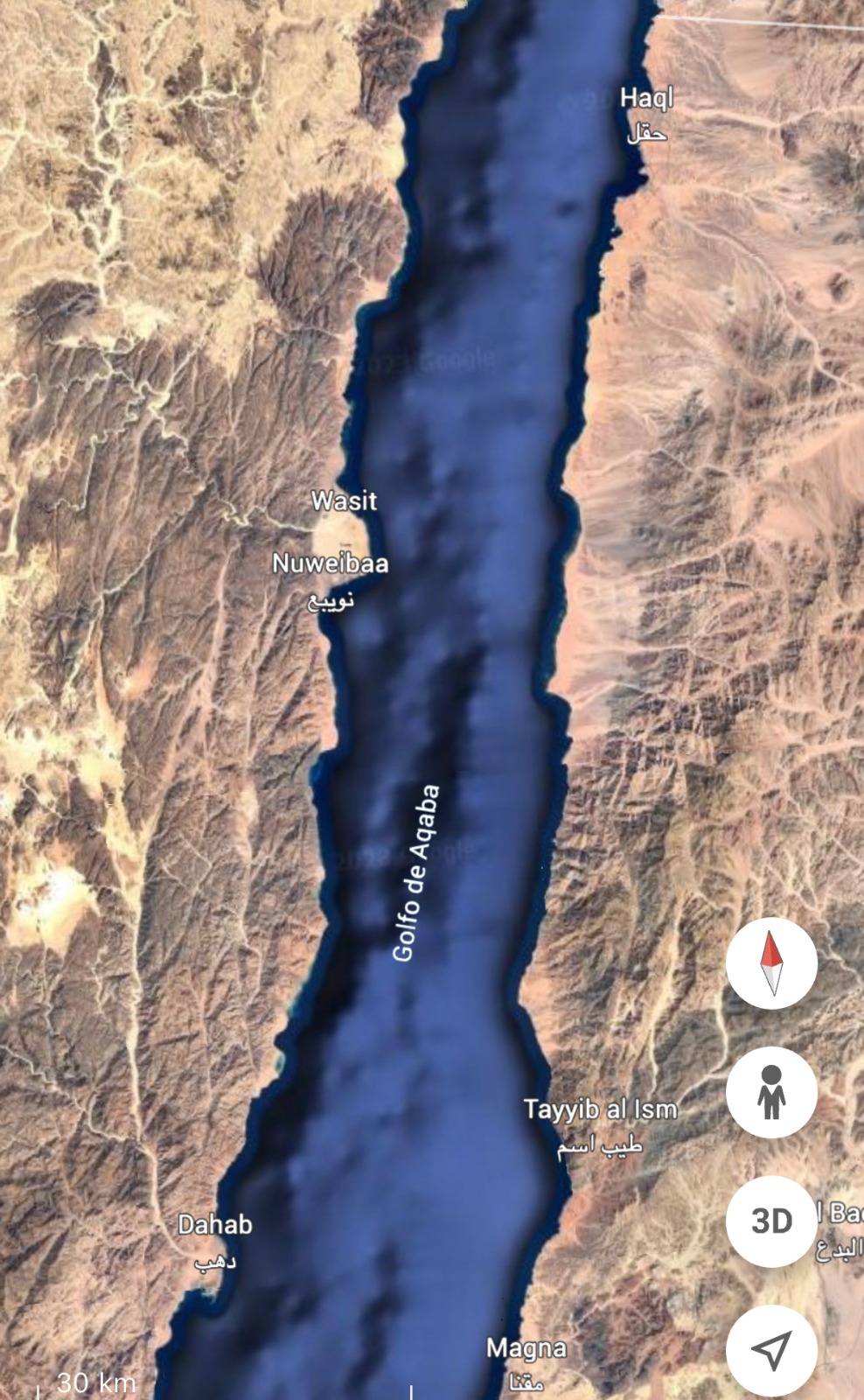

A careful and detailed biblical reading confirms this verification. Medieval maps indicated Midian, the land of Jethro (Reuel), on the Arabian Peninsula. The German historian and journalist Werner Keller described Moses choosing “for his exile the mountains of Midian, east of the Gulf of Aqaba, a region in which there was a remote connection,” because “Midian was the son of Keturah, Abraham’s second wife, later of the death of Sarah” (The Bible as history, p. 123). In the Old Testament, the members of the tribe of Midian are known as Kenites. Professor James Alan Montgomery, from the University of Pennsylvania, details the area between the Nile River and the Gulf of Aqaba (Elanitic) as “under Egyptian influence,” known to the Arab peoples as “MRS, that is, Misraim” (Arabia and the Bible, p. 31), ancient name of Egypt. Therefore, the Sinai Peninsula has always been configured as an Egyptian protectorate.

If the Sinai Peninsula was in Egypt when Moses led the people “out of Egypt” and into Midian, then they crossed the Gulf of Aqaba to the Arabian Peninsula, never the Gulf of Suez to the Egyptian peninsula. If Mount Sinai was really located on the Sinai Peninsula, the Israelites would not leave Egypt, contrary to the text in which the Divine order that they would leave Egypt is read (Ex 12:41). When Moses defended the seven daughters of his future father-in-law from the onslaught of enemies when they were trying to fetch water from a well for the flock, they considered him to be an Egyptian, belonging to another, foreign country (Ex 2:16-9).

Later, Moses married Zipporah, one of the daughters of the farmer Jethro, with whom he had two children. He called the oldest son Gershom (“Gerson”), the “immigrant”, “foreigner,” given that he claimed to be “a pilgrim in a strange land” (Ex 2:22). In the unusual encounter at the sacred mountain of Horeb, God asks him to return to Egypt (Ex 3:7-13). In other words, Moses lived in Midian, and not in Egypt (Ex 3:1, 11 and 12), but he would return with his people to worship the Lord in that same place, in Midianite territory.

Egyptian Sinai

The Roman emperor Constantine the Great (280-337 A.D.) claimed to have many visions in 312, in one of which he imagined contemplating Mount Sinai, precisely in the region where the Monastery of Saint Catherine would be built. Researchers, archaeologists and historians credit him with inventing the name of this mountain. Emperor Justinian built this monastery in 527 A.D., on the site where Helen, mother of Constantine, built a chapel two centuries earlier, on the northwest slope of the Jabal Musa, known as Sinai (The interpreter’s dictionary of the Bible, p. 376).

The philologist Frederik Christian von Haven participated in an expedition to Yemen and the Sinai Peninsula, visiting the monastery. Mentioned by writer Thorkild Hansen, Von Haven realized “from the beginning that it couldn’t be Mount Sinai. The monastery is located in a narrow valley, not wide enough to allow an army of medium size to camp, much less the 600,000 men led by Moses, who, together with women and children, should exceed three million” (Arabia felix: The danish expedition 1761-1767, p. 181).

You don’t need to have a lot of common sense to be suspicious of an environment without any precise archaeological remains. Hundreds of thousands of people camped for years would leave evidence of their presence for posterity. The mountain itself does not feature any points or types of stones associated with the factual details of the Israelite camp mentioned in the Pentateuch.

According to the Bible, the people of Israel left Ramesses for Succoth (Ex 12:37), in the region of Goshen. They surrounded it near the Red Sea, camping in Ethan (Ex 13:18 and 20). Then they turned back and remained “in front of Pi-Hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, in front of Baal-Zephon” (Ex 14:2). The maps present in the Bibles do not locate the same points mentioned. There are disagreements among philologists, geographers, historians and archaeologists.

Gulf of Aqaba

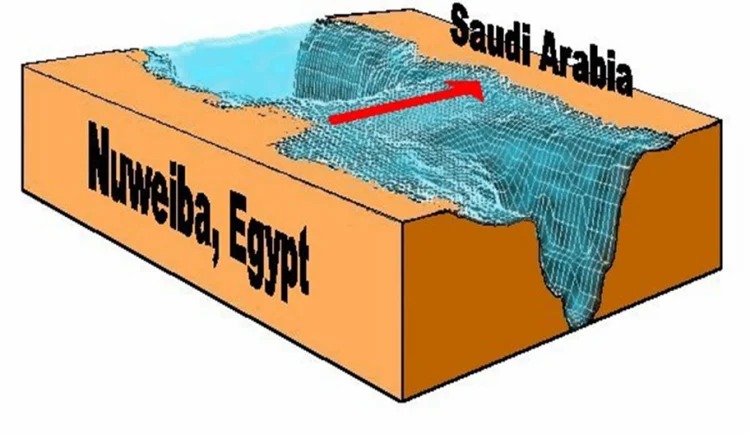

Ron Wyatt points to Nuweiba beach as the most suitable place to receive more than two million individuals. Located in the Gulf of Aqaba, it faces the Arabian Peninsula, in which the Midianites lived. In Nuweiba there is evidence of the Israeli presence. Surrounded by hills, anyone arriving from the north would be trapped on the beach, with only the waters of the gulf in front.

On the Egyptian side there is a column with inscriptions in ancient Hebrew, reporting the escape from Egypt, just as on the Saudi side there was another column, replaced by a flag marker. When an event became significant for a people, it was customary to record it at the place of occurrence. On the opposite side of the Egyptian peninsula, the column recorded the sequence of words, probably with additions over the centuries: Egypt-Solomon-Edom-death-Pharaoh-Moses-YHWH. It looks like a historical salad, but it offers the dimension of the Hebrew presence in the place on many occasions. When starting and completing the crossing of the eastern arm of the Red Sea, the Israelites celebrated (Ex 15:1-20) and marked these locations.

That point in the gulf is the shallowest, with a maximum of 110 meters. They found there a human femur and ribs, Egyptian chariot wheels with four, six and eight spokes, some plated with silver and gold, most likely officers’ carriages (Ex 14:7). This strip of sea looks like a flat path, without obstacles, but enough to drown the Egyptians. There are rocks lined up on both sides, like the limit of a route to follow.

Jabal Maqla/Al-Lawz

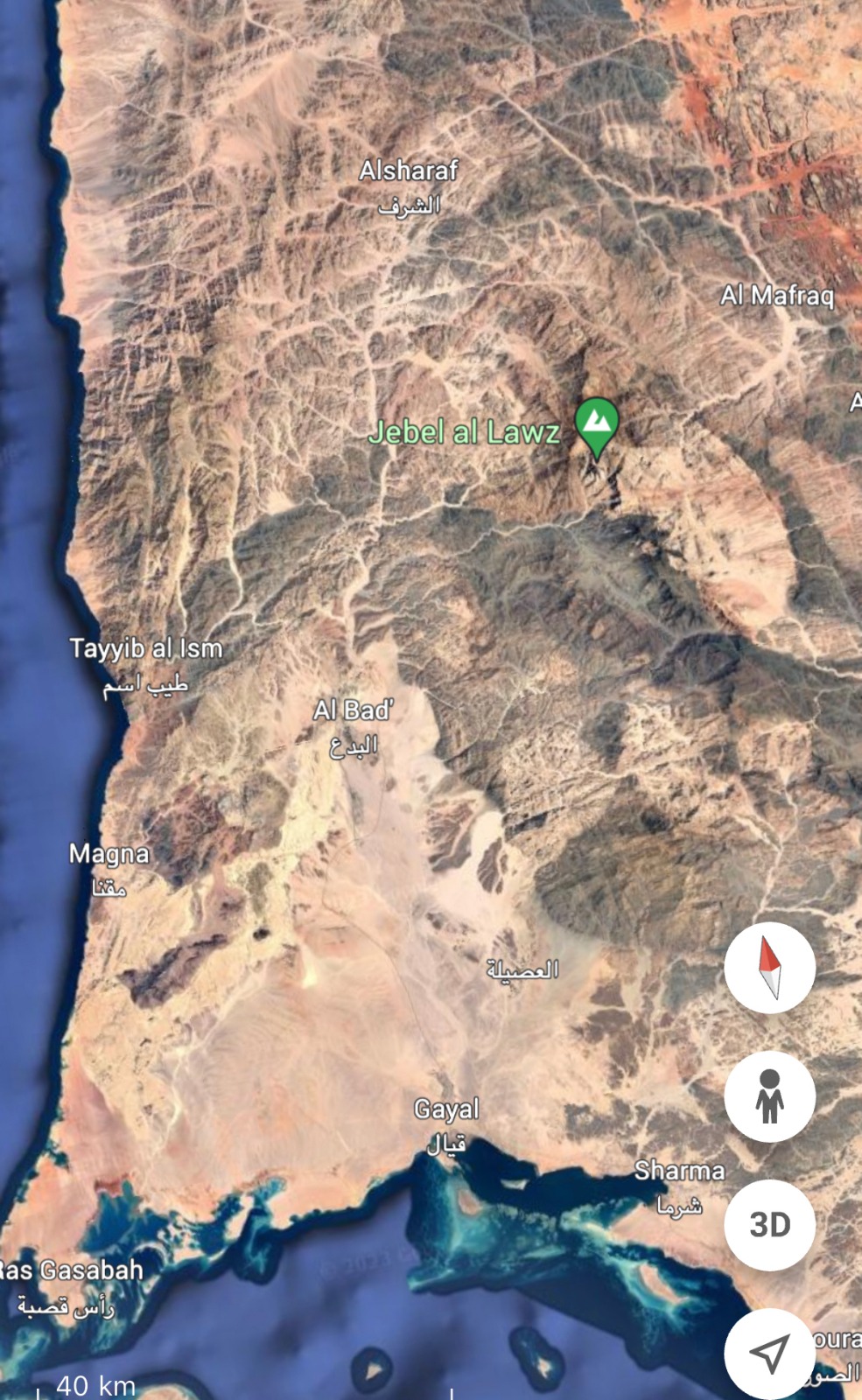

On the other side of the Gulf of Aqaba, the eastern arm of the Red Sea, in present-day Saudi Arabia, are the mountains Jabal Maqla and Jabal al-Lawz, southeast of Nuweiba. Jethro probably lived southwest of the mountain, in the region of present-day Al-Bad. In and around the mountain there are signs of human presence in a very distant time.

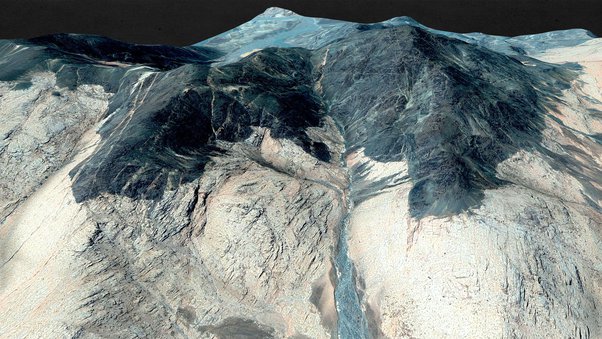

Unlike the surroundings of Jabal Musa, in the Sinai Peninsula, it is possible to accommodate more than two million people in front of Jabal Maqla. Even today, there is vegetation for animal husbandry. Rephidim, the site of battle against the Amalekites, should be located northwest of the mountain (Ex 17:8). Moses reported that the Lord had ordered stones to be placed delimiting the perimeter as far as the people could approach. These stones are positioned close to the mountain (Ex 19:10-2 and 23), as well as supposed altars (Ex 32:3 and 4; 20:25), the landmarks of the conquests attributed to the twelve tribes (Ex 24:4), a cave or grotto, in which Moses remained and, years later, the prophet Elijah (Ex 33:21-2), evidence of the passage of a stream (Dt 9:21) and the blackened top of the mountain (Ex 19:16 -8). From Arabic, maqla means “burnt,” that is, a mountain that in the past smoked, according to the Holy Scriptures.

Jabal Maqla is located in the set of Saudi mountains called Madiyan (Midian). Some archaeologists, including Wyatt and the renowned Robert Cornuke and Lennart Möller, consider another mountain, Jabal al-Lawz, located seven kilometers to the north and higher, as the one referring to Mount Sinai. When consulting Google Maps and searching for Jabal Maqla, the “altar of Moses” appears on the eastern side, also verified by Google Earth. However, when searching for Rephidim, the automatic enlargement brings it closer to Jabal Maqla, containing below the term “Mount Sinai of YHWH” (Yahweh, Yahweh, Jehovah).

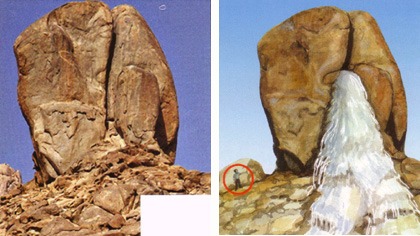

The Israelites left Succoth (Ex 13:20), north of the Gulf of Suez, and camped in Ethan, north of the Gulf of Aqaba, at the edge of the desert. Then they headed for Nuweiba, further south, in the middle of the gulf. Both gulfs make up the Red Sea (I Kings 9:26) as extensions, arms. After planting stakes in Rephidim, the people became angry with Moses because there was no drinking water (Ex 17:1-4). Near this location, researchers found a rock with particular characteristics. The crack that apparently divides it appears to be the point through which water passed and caused erosion on the land and also on the small rocky structures in front, supposedly running along a riverbed (Ex 17:6 and 19:3).

Just below the broken rock is an altar. It can be deduced that the Hebrews erected it in remembrance of the victory over the Amalekites, when they confirmed the Lord as their “banner” (Ex 17:15-6), right in front of Jabal Maqla, or Sinai (Ex 24:4). Geologists confirmed the presence of the bed of a supposed watercourse, whose torrent descended from the mountain. Furthermore, at the site of a possible oven, there is a drawing of a bull (Ex 32:4, 5 and 19), the only inscription of this model in the entire Arabian Peninsula.

Due to the descent of the Lord like fire on Mount Horeb, causing smoke to rise, similar to that coming out of a furnace, shaking the mountain, the upper part of both mountains – Jabal Maqla and Jabal al-Lawz – appears completely darkened in relation to the rest of the landscape below and the surrounding mountains. Elijah fled from Queen Jezebel, wife of King Ahab, of Israel, and took refuge in a cave in the mountain of God (I Kings 19:8 and 9), existing in the massif, which does not occur in “Sinai” on the Egyptian peninsula. Could this have been the place where Moses stood before receiving the Decalogue and where he caught a glimpse of the glory of God?

It is true that today there is no way to get there, as it is a militarized zone, exclusive to the Saudi armed forces. Not even satellites can make out details of this region. The following warning appears: “Archeological area. Warning. It is unlawful to trespass. Violators are subject to penalties. Stipulated in the antiquities regulations. Passed by royal decree n. M26, D 23/6/1982 (1352).” Even though it indicates a research zone, no one can get closer to said mountains.

Reinforcement of faith

As long as the state of ideological, political and religious belligerence continues, it is unlikely that researchers will access the promising sites of the Saudi mountains Jabal al-Lawz and Jabal Maqla with permission and safety. Perhaps to prevent the veneration of the place, the Lord considered its inaccessibility prudent, given the erratic trade established for centuries at the foot of false Sinai, next to the Monastery of Saint Catherine, in Egypt, on the western side of the gulf.

This analysis serves very well for other important geographic points determined to be sacred to the Islamic, Jewish and Christian universes. The invention of pilgrimage sites only serves to boost the economy, the religious industry of speculation.

On the other hand, knowing the details present in these historical areas reinforces the certainty of the veracity of the biblical textual narrative. The geographical, geological traces, pieces and drawings corroborate faith in the logical structure of the God’s Word, increasingly encouraging the sincere at heart to delve deeper into the study of the Bible, preparing themselves for the climax of the story, the return of Jesus.

Ruben Dargã Holdorf

Doctor in Communication and Semiotics.

Worked as a History teacher at Boqueirão Adventist School, in Curitiba, from 1991 to 1999, and in the History degree at Unasp, in 2013. He edited the column “Arqueologia e Ciência” (Archeology and Science), from 1997 to 2006, for Paraná Online, the portal of the newspapers O Estado do Paraná and Tribuna do Paraná. For two decades he taught History of the Press for the Journalism degree at Unasp, and also History of Foreign Journalism at UGI, in Butcha, Ukraine.

Leave a comment